It seems we can’t find what you’re looking for. Perhaps searching can help.

It seems we can’t find what you’re looking for. Perhaps searching can help.

An opera in three acts about parental ambition

April 28-30 2022

See the trailer here on YouTube in a new tab.

Review by The Guardian Fri 29 Apr 2022

“A timeless story of parental harm done to children”, is composer Michael Zev Gordon’s description of the myth of Daedalus and Icarus. His Icarus opera has been a long time in the making; in 2011 he wrote a brief theatre piece based on the legend, but Raising Icarus, staged by Barber Opera, is the real thing, an impressive full-length chamber opera, to a libretto by Stephen Plaice.

It tells the story of the smith Daedalus and his ultimately tragic ambitions for his son in three succinct acts: from Icarus’s failure to be the kind of skilled craftsman his father wants; through Daedalus’s indebtedness to Minos, the ruthless, impotent king of Crete, whose wife, Pasiphaë, is infatuated with a bull by whom she has a child; Daedalus’s building of the labyrinth to contain that monstrous offspring, the minotaur; the father and son’s escape from it on the wings that Daedalus makes for them; and Icarus’s fatal, hubristic flight.

Plaice’s unselfconsciously rhymed text presents the narrative very clearly, if occasionally just a bit too wordily, but Gordon’s setting of it, mostly in graceful arioso phrases, ensures that the sense come across easily. Only the vocal lines for Pasiphaë, louche and languorous with a bluesy tinge, are especially characterful, but each of the leads is crisply defined nevertheless. The ending, when four of the characters come together as a Greek chorus to reflect on Icarus’s fall, is beautifully handled. Underpinning the singers there is a quirky, rather astringent eight-piece ensemble (Birmingham Contemporary Music Group), which includes an accordion and a trombone, and provides pulsing, restless accompaniments, full of ear-catching detail. Sometimes it erupts in tangled, menacing climaxes.

The modern-dress staging by Orpha Phelan is effective enough, if occasionally rather fussy and twee, but the performances – led by James Cleverton as the bullying Daedalus and Margo Arsane as the pliant Icarus, with Andrew Slater as Minos, Galina Averina as Pasiphaë, Lucy Schaufer as Polycaste and William Morgan as her son Talus – are all strong. And Natalie Murray Beale’s conducting ensures that the drama, very well paced by Gordon and Plaice, packs a punch.

A comic opera in four acts

A post-Brexit comedy set in the fictional Southern town of Melhaven. The announcement of the winner of a national competition to regenegerate the coastal towns is imminent. The Mayor has pulled out all the stops, hoping to boost Melhaven’s bid for the money to save the declining resort. But it only survives on its black economy, and when the judges arrive for their final inspection the cracks start to appear, not only in Melhaven but in post-Brexit Britain as a whole.

The first act of Bloom Britannia was performed at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill in April 2019. Three performances of the full opera, with a cast of over a hundred singers, were given at St Mary in the Castle to great acclaim in October 2021.

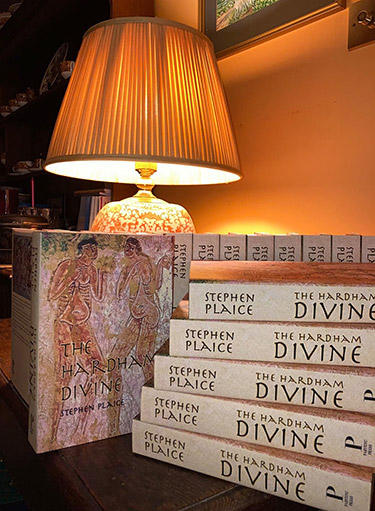

The novel describes the terror and beauty of a medieval Sussex ravaged by famine and drought where, taxed to the bone, the poor wait for a leader to deliver them. Set in the turbulent years between the first and second Crusades, The Hardham Divine tells the story of Truda, a young Saxon woman, who finds herself the centre of a messianic uprising.

For more information go to: parvenupress.co.uk/publications

Set in a Parisian market, this hilarious one act operetta was commissioned by Glyndebourne for performance in the gardens throughout August. Stephen collaborated with Marcia Bellamy to produce a new version of Offenbach’s 1858 hit, directed by Stephen Langridge. The new version is entitled In the Market for Love or ‘Onions are Forever’.

Having previously worked with Marcia to produce Offenbach’s work in Bouffe!, Stephen was delighted to be part of the creative team bringing Offenbach to Glyndebourne for the first time, as part of their artistic response to the challenges of COVID-19.

“Wittily reworked by Stephen Plaice…Mesdames de la Halle is an Offen-ready treat.”

The Observer

“There’s a thrown-together, on-the-hop feel to it – the set is clearly a raid on the company’s store house – but it’s a full staging, with first-rate singers and a small but polished … That’s several causes for celebration right there.”

The Guardian ****

“In the Market for Love is a slight, daft piece and the gamble of this “Covid” production by Stephen Langridge, with a new English libretto by Stephen Plaice, is that it pushes to the foreground the things that some of us might like to forget, at least for an hour: masks, visors, 1/2/3-metre rules, squirts of sanitiser.”

The Times ****

“With boisterous direction, and the whole cast romping cheerfully over Offenbach’s bouncy galops and flirtatious waltz songs, it’s surely the most fun any of us will have in the opera house for the foreseeable future, and a million times more helpful, right now, than the incoming tide of earnest new-music commissions about the trauma of lockdown.”

The Spectator

“Irrepressible energy, irreverent wit and a terrific ensemble performance bring some brightness into the prevailing gloom.”

The Stage ****

An opera in four acts

The Tale of Januarie is a collaboration between composer Julian Philips and writer Stephen Plaice. It is based on The Merchant’s Tale from Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. A comedy of love and age, the opera’s libretto is in Middle English in order to enhance its authenticity, but also to heighten the comedy. It was produced and performed by an all-Guildhall School team, and staged to great acclaim at the Guildhall’s Silk Street theatre in 2013. The première in 2017 was sung by singers drawn from the School’s Opera Course, who had followed its development from page to stage.

The Tale of Januarie was warmly received by the UK national press, with four star reviews in the Guardian, Financial Times and Sunday Express.

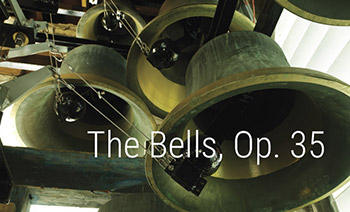

Stephen has produced a new translation of the libretto of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s The Bells (Opus 35). The work was composed in 1913 to a libretto by the Russian surrealist poet Konstantin Balmont who had freely adapted Edgar Allan Poe’s poem The Bells.

The new English translation, with English text setting by Marcia Bellamy, attempts to bring the libretto closer to Poe’s original poem. It was premièred in the Barbican Hall on Friday 27th September 2019 by the Guildhall Symphony Orchestra and the Guildhall Symphony Chorus, conducted by Dominic Wheeler.

John Faust, a young mathematician, enlists the help of Mephistopheles to solve the secret of prime numbers.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Jon Dickinson

Designed by Alix Parker and Jon Dickinson

Cast: Christopher Wilson, Damian O’Donovan, Sharon Jones

Première – The Marlborough Theatre, Brighton: 1986

Edinburgh production: August 1986

Press notices

‘The actors seem to have fallen in love with the play.’

The Stage

‘A great deal to think about if you can follow the twists and turns of the author’s dialectic.’

The Scotsman

Adaptation of Georg Büchner’s play by Stephen Plaice

The Prince of Popo and the Princess of Popo run away to avoid an arranged marriage, only to meet and fall in love with each other on the run.

Directed by Stephen Plaice

Designed by Nick Martin

Cast: Damian O’Donovan, Karl Moses, Chris Wilson, Alex Evans, Nicola Jones, Aliss Moss

Première – The Nightingale Theatre, Brighton: 5th May 1987

Brighton Festival Theatre Award Winner

A prison teacher is caught in a triangular relationship with a prison officer and an arsonist who believes he is the son of God.

Play written and directed by Stephen Plaice

Designed by Matthew Miller and Jane Sybilla Fordham

Cast: Damian O’Donovan, Janette Eddisford, Steve Middleton

Première – The Nightingale Theatre, Brighton: 20th October 1987

An adaptation and reconstruction of Aristophanes’ fragmentary play by Stephen Plaice

Dissatisfied with their husbands’ performance, the women of Athens decide to run things for themselves.

Directed by Helena Uren and Stephen Plaice

Designed by Jane Sybilla Fordham and Matthew Miller

Cast: Alex Evans, Damian O’Donovan, Dominic Mann, Ralf Higgins, Judi Heppell, Peta Taylor, Judith Hurley, Nicola Jones

Première – The Pavilion Theatre, Brighton : November 1989

A perestroika adaptation of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s play by Stephen Plaice

In the 1990s, Prisypkin, a Russian Yuppie, is cryogenically frozen after a fire destroys his wedding. He is defrosted in a European superstate fifty years later.

Directed by Helena Uren

Designed by Anna Symes / Graham Evans

Moscow production designed by Matthew Miller

Cast: Ralf Higgins, Judith Hurley, Daniel Earl, Mim King, Kate Gisbourne, Allison Hudson

Première – The Pavilion Theatre, Brighton: February 1990

Edinburgh production: 20th August 1990

Moscow production: 5th September 1990

Press notices

‘ Stephen Plaice’s bold and for the most part effective adaptation for Alarmist Theatre transplants the first act to post-perestroika Russia in 1990, then has the hero, Prisypkin, waking up in the year 2040 with a grave new dehumanised capitalist world in which the chief human right is to consume, and romance is found only in the dictionary of obsolete terms.’

Mick Martin The Guardian

‘Lively update, shot through with witty and topical one-liners and performed by a fivesome that’s young nifty and slick.. Alarmist’s moving and memorable seventh show looks good and feels good too. Laugh first, and think afterwards.’

City Limits

‘Superb staging of updated satire. Mayakovsky would undoubtedly have approved.’

The Scotsman

‘ Alarmists cause laughter in capital theatres. Played to packed houses in Moscow.’

Soviet Weekly

The life of the playwright and secret agent Christopher Marlowe, examining the conspiracy that led to his death in a Deptford tavern.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Helena Uren

Designed by Matthew Miller

Cast: Jason Merrells, Catherine Gisbourne, Matthew Haynes, Ralf Higgins, Simon Morales, Judith Hurley, Sebastian Michael

Première – Pavilion Theatre, Brighton: May 20th 1992

Edinburgh production: 17th August 1992

London Première – Warehouse, Croydon: 9th September 1992

Press notices

‘The whole company ignites this sometimes grotesque vision of plotting to provide an exceptional homage to Marlowe. Through literature and history it formulates a wonderful and arresting story.’

The Scotsman

‘Admirably played by a talented cast who strut and fuck with vigour. A hoot.’

Time Out

‘The play skilfully combines masque and music with the darkness and brooding cynicism of Revenge tragedy to create an absorbing spectacle’

The List

‘ The Warehouse has it taped early with this boisterous and, for all its occult posing, amiable show from Alarmist Theatre, which flits in fresh from its midnight slot at the Pleasance.’

‘Ralf Higgins is a visually striking Marlowe, ashen-faced, hollow-eyed, red hair cropped short, but his prancing, preening performance suggests Kit was killed because Elizabethan England had room only for one queen.’

Martin Hoyle The Times

‘Claptrap’

The Kentish Times

A criminal review, scripted by Stephen Plaice and John Williams

The life of armed robber John Williams is related in a series of sketches that take the lid of the Criminal Justice System from the inside.

Directed by Helena Uren

Cast: John Williams, Stephen Plaice

Première – Sallis Benney Theatre, Brighton: 7th May 1993

Edinburgh Festival production – De Marco European Art Foundation: 16th August 1993

A farce about the changing nature of work

Mr Lightvessel, an estate agent, who is also a volunteer lifeboatman, tries to stay solvent in the face of a frozen house market. Already paying his staff so little they have to sign on as well as working, he strives to complete a chain of sales that will save his business. Unfortunately the vital link in the chain is a dole-fraud investigator.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Alison Edgar

Designed by Katherine Lara

Cast: Tristan Sharps, Ruth Burton, Geoffrey Maltman, Ian Angus Wilkie, Liz King

Première – The Hawth, Crawley: 15th November 1995

Press notices

‘If there was any doubt about the strength of the Hawth’s resident company, Shaker productions, or the writing skills of Stephen Plaice, then last week’s Home Truths quickly dispelled it.’

West Sussex Gazette

‘After such a promising start, the play develops into complete farce’

The Stage

A short comedy – no. 3 of a trilogy

Two bidders for the same contract arrive at the sorting office just in time for the last post. The Man has the stamps, the Woman does not. He agrees to let her have the necessary stamps if she reveals the bottom line of her company’s bid.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Alison Edgar

Designed by Katherine Lara

Cast: Sally Phillips, Tristan Sharps, Trevor Penton

Première – The Hawth, Crawley: 29th March 1995

London Première – Lyric Studio, Hammersmith: 21st April 1997

Press notices

‘excellent’ West Sussex Gazette

‘perfectly inoffensive’ Time Out

A short comedy – no. 2 of a trilogy

Three candidates arrive for an interview, two men and a woman. During their tense wait outside the interview room, they begin to reveal animal characteristics.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Alison Edgar

Designed by Katherine Lara

Cast: Tristan Sharps, Trevor Penton, Alison Edgar

Première – The Hawth, Crawley: 27th March 1996

A short comedy – no. 1 of a trilogy

A man who has written a farewell letter to his wife finds his mistress in bed with another man. He has to get the first train home in order to retrieve the letter and save his marriage.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Stephen Langridge

Designed by Sophia Lovell Smith

Cast: Maggie O’Brien, Julian Parkin, Tristan Sharps

Première – The Hawth, Crawley 26: November 1997

In 1934 Tony Mancini was acquitted of the murder of Violette Kaye whose body he had stored in a trunk. Forty years later he confessed to her murder. But this was only one of the two bodies found in trunks in Brighton in the summer of 1934. The second victim, known only as the Girl With Pretty feet, was never identified, nor was her murderer.

Play by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Alison Edgar

Designed by Henk Shutt

Music Richard Ball

Cast: Ruth Burton, Gregor Truter, Trevor Penton, Lucy Maurice, Kate Fenwick, Lorien Hayes, Emilia di Girolamo, Lucy Taylor, Dom Boydell, Stephen Plaice

Première – The Hawth, Crawley: 17th November 1993

London première – Battersea Arts Centre: 29th March 1994

Transferred to Studio Lyric Hammersmith: 12th July 1994

Press notices

‘A lively essay in the macabre, recreating the Brighton Trunk Murders of 1934 which led that famous seaside resort to be dubbed Torso City. Clearly influenced by Graham Greene and Patrick Hamilton, Plaice’s text and Alison Edgar’s complementary production also explore the raffish seediness of pre-war Brighton.’

Michael Billington The Guardian

‘Alison Edgar’s stylish and smoothly choreographed production combines trash with tango culminating in a truly impressive sawing-in-half’

Paul Paul Taylor The Independent

‘Shaker productions assemble a powerful production of Stephen Plaice’s study of the desperate fall-out of the Depression era.’

Time Out Critic’s Choice

Strongly recommended. See it. If you can get a ticket, that is.’

What’s On

“What is the point of this sordid little story? I am not sure, and I am not sure the author is sure.’

Benedict Nightgale The Times

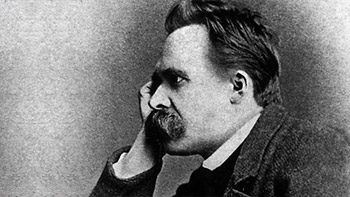

Stephen ends his philosophical journey in Berlin where he considers how, in maintaining our prejudices towards the Germans, we have excluded the liberal wisdom of its philosophers. Berlin, a city with an very divided past, provides a living metaphor of the Hegelian dialectic of history. Out of the opposing forces of Communism and Nazism, a third, democratic synthesis has emerged. But at Checkpoint Charlie, Stephen discovers that the old oppositions of the Cold War have been turned into tourist entertainment. Is there an ironic phase to history?

Visiting the cemetery in which Hegel is buried, and then the Humboldt University where he lectured, Stephen reflects on the two opposing ideologies that tried to gain control of Berlin in the 20th century, and examines the extent to which the accusation holds that German idealist philosophy was responsible for the rise of both Fascism and Communism. He cites Kant’s treatise On Perpetual Peace to illustrate the enlightened legacy which has been obscured behind the pseudo-philosophy of the Third Reich. Stephen argues that we have handed Hitler a victory by allowing our image of the Germans and of German culture to remain fixated on the Nazis.

Stephen also reflects on The Principle of Hope, a key work by the German Jewish utopian philosopher Ernst Bloch, which he co-translated in the 1980s.

In conclusion Stephen reflects how, from the early Romanticism of student days in Germany, via Nietzsche and Schopenhauer, to Ernst Bloch’s philosophy of hope and the Kantian responsibilities of parenthood, philosophy has the power to shape personal experience.

Stephen visits the Nietzsche House in Naumburg, in the former East Germany, where Nietzsche spent part of his youth and where he returned at the onset of his madness.

He meets the head of the Nietzsche Archive, Rüdiger Schmidt Grepaly, and Fellow in residence Stefan Wilke. The archive is housed in the house where Nietzsche died, having been removed to Weimar by his ambitious sister Elizabeth Förster Nietzsche on the death of their mother.

Grepaly and Wilke explain the triangular relationship between Nietzsche, his friend, the psychologist Paul Rey, and a beautiful and brilliant young student Lou Andreas Salome. The relationship ended in disaster for Nietzsche when the other two abandoned him to a life of hermetic isolation.

Stephen compares this relationship to the three-cornered friendship between himself, his Nietzschean school friend Kevin and Maja, a beautiful doctor’s daughter, when they all lived in Zurich in the late 1970s. Stephen’s romantic hopes were finally dashed when Maja declines to accompany him on a nocturnal ski sortie across a frozen lake in the Alps, close to where Nietzsche wrote many of his major works. In the freezing temperatures, the limitations of the Nietzschean path become all too apparent to the lonely skier.

Stephen is reunited with Maja in Berlin. They recall Kevin and the events of that time together. Stephen realises he was unable to live up to Nietzsche’s demand that man should transcend his humanity and become the Superman.

Together with his brother Neville, an expert on the romantic city of Heidelberg, Stephen explores the city of the Student Prince and examines its connections with the philosophers Hegel and Schopenhauer. He considers the idea of the Doppelgänger, the double, an important archetype in German Romantic literature.

Neville explains how the movement of High Romanticism was created by the anti-French nationalism, which developed in the city during the years after the Napoleonic invasion. The enthusiasm for German folklore, which was later fostered by the Nazis, was directly related to this cultural reaction.

Stephen discusses with his brother two of the famous philosophers associated with the city, Hegel and Schopenhauer. Hegel went on to become an intellectual superstar, taking over the chair of philosophy in Berlin. Schopenhauer, on the other hand, was dismissed by the academic establishment, his ideas only latterly being taken seriously by the likes of Richard Wagner and Friedrich Nietzsche. Schopenhauer attempted to emulate Hegel, and became a kind of Doppelgänger for him when he followed in his footsteps to Berlin and set up his own rival series of lectures. These were so poorly attended however, he had to beat an ignominious retreat from the capital.

Stephen visits the Russian city of Kaliningrad, formerly Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia, to explore the legacy of the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who lived his entire life in the city.

He visits Kant’s grave and meets Kant scholar Vadim Chaly, a native of the city which Stalin ethnically cleansed of Germans in 1946. He also tracks down Professor Vladimir Bryushinkin, the current encumbent of the Chair of Logic at Kaliningrad University, the chair that Kant once occupied in the old city of Königsberg.

Stephen revisits Marburg, where he was a student 35 years ago. He reconsiders the subjective philosophy of Fichte and of the nature philosopher Schelling, whose work he studied in the 1970s, with particular reference to Schelling’s idea of the World Soul.

These thinkers provided the philosophic basis for German Romanticism. Stephen relates how, as a young man, seeing the world through the lens of Romanticism, he was in for some pretty sharp collisions with reality.

The ‘magic theatre’ behind the mysterious black door in the building in which he rents a room as a student turns out to be Marburg’s secret gay scene. Revisiting the building nearly four decades later, he discovers it has become another cultural ghetto: a smoker’s pub.

Stephen also recalls a house party in the forests near Marburg back in the early 1970s, where he had a strange encounter with a young woman who seemed to embody Schelling’s idea of the World Soul. Like a character in a fairytale, she appears to have sprung from the forest itself. However, the inherent romanticism in their meeting is later tempered by the appearance of the woman’s husband.

A dramatic oratorio

A sonic souvenir of Brooklands and the golden age of motor racing. This site-specific event was staged at the Barnes Wallis Stratosphere Chamber, Brooklands Museum July 14 2018

Text: Stephen Plaice

Music: Joanna Lee

Director: Lucy Bradley

Musical Director: Lee Reynolds

Design: Nik Corrall

A sample poem from the collection

Giants

Mother, I’m meeting my nightmares,

the giants that hushed me when you read.

Here is the castle where Giantkiller Jack

came to sever their one two three heads

with the sharp little sword

the Justices of Cornwall lent.

I had to see the pictures before I slept,

just to make sure the giants were dead.

Mother, I’ve crawled up the beanstalk,

to be in the House of Fear we built back then,

where many last prayers went unheard,

and a sack swung slow on a beam.

Mother, you wished me sweet dreams,

but we never in our wildest thought

I’d end in the place reserved for the frights

which lurked behind every tree.

Mother, I’m meeting the headlines in the flesh,

the ones you wouldn’t let me see.

Here is the rabid fiend

Who chased me across the foggy heath.

Here are the flabby hands

that squeezed until I couldn’t breathe.

Mother I can hear him singing,

and I know he’s coming for me.

Shaven bonce, low brow, scowling mien,

now he’s here, right in front of me,

the worst of the worst grown tall

the one they could never reprieve.

He wants to know if you’re still alive,

and chides me for having no children.

Sometimes he even calls out your name

Behind the door, when they put out the lights.

Mother, it’s safe in here, safer than houses

where I slept as a child and dreamt

of these very men coming to get me,

but it’s me who has come to get them,

with the sharp little pen the Justices lent.

Mother, I’m just writing to let you know

I have got inside the book we read

where the beast craves the gentleness you gave me.

A sample poem from the collection

Photosynthesis

When photography began, the world stopped.

The pony and trap held patiently still.

The farmer’s wife in the doorway turned to stone.

The labourer with shouldered pitchfork

stiffened into his respectful pose ten paces

from the awkward earl enacting his daily stroll.

Only the unruly tree continued to swirl,

filtering the pale summer sunlight,

spoiling the edge of the treated plates.

When our ancestors began to picture themselves,

they wished to preserve their stationary world,

even though this is also the very moment

from which we have measured its decline.

The labourers went quietly into the factories,

land values rose, the farm was sold, resold,

the track became a lane, the lane a road

which still bore the farmer’s family name,

but a hundred families came to call home.

Slowly the pictures too began to move

and to occupy us for whole hours of the day.

Now we sit and watch a moving world,

see more than we could imagine alone

or ever experience for ourselves.

We observe the acts of love and death so often

– even follow the salmon journey of the sperm

– and the transmigration of our astral souls –

they no longer move us to pleasure or to tears.

But sometimes when the images pall

and we step out, no further than the gate,

for a breath of the half-refreshing air,

stand motionless among the cars,

surveying the life of our suburban road,

it feels like we too are being observed

by something much more ingenious –

and there is the tree still absorbing light,

the oldest camera in the world.

A sample poem from the collection

The Man Who Steals Behind Me

When turning back on certain roads,

I have seen the conspiring trees conceal

the man who steals behind me,

all that I have known he knows,

all that I have felt he feels.

Along the paths my feet have trodden

he whistles the tunes I have forgotten,

rambles through my neglected days,

blown by the aimless winds

that play down unadopted lanes

and sweep the cold, deserted fields.

When turning back in certain towns,

I have seen a closing door conceal

the man who steals behind me,

all that I have thought he thinks,

all that I have coined he steals.

In bars where former friends still drink,

He refills the glass I drained,

spouts the stale ideas once framed

in the bright and bevelled mirrors

where my spitting image revelled

with my forsaken companies.

When turning back on certain rooms,

I have seen a shifting eye conceal

the man who steals behind me,

all those that I have loved he loves,

all those that I have hurt he heals.

In last night’s hotel he entertains

women in whose arms I have lain,

repeats my plausible appeals

to pretty felicity to marry me

and live as plain fidelity.

He sleeps with my missed eternities.

When turning back on certain roads,

I have seen the growing dark conceal

the man who steals behind me.

He is the space that I have filled,

all that I become, he is still to be.

Once I thought he followed,

but the longer that I walk I feel

that man steals away from me,

and there beyond the furthest tree

it is not a death that stalks behind,

but a life departing from my heels.

A sample poem from the collection

Canal Time

Down by the hump-backed bridge,

where the Grand Union

sets the pace of midsummer,

I watch my sons wind the windlass,

lean their backs into the beam

and swing the mitred lock-gates

to help the barges through.

Such work is leisure now,

but the bargee’s boy has the accent still,

tells me he’s turning fifteen,

the age I must have last fished here,

with my back to this red-brick mill.

It’s inhabited now, rustique,

drying-holes glazed to lights.

sills planted with geraniums,

the wharf gone to grass and cycle path.

I lend my back to the beam.

A waft of weed, silt and fish.

The sense of something moving far below,

as if I were pushing at a gate

into a slower scape of time,

before these willows took their shape,

when the mill breathed out its malted breath

into the chugging, coal-smoked afternoon.

But it’s not the past returning,

rather the present that extends –

the birds moving in their continuum,

the minnows rising, their perfect rings,

the bargee tinkering with his engine.

Call it canal time, the lower pulse

that beats, for example, in the tree,

a kind of witness, without memory.

And for the duration of that swing,

our feet overlap with all those

who pushed upon these iron steps,

with those who will follow yet

this custom by the water’s edge,

as if a giant key were turned

to unlock the living moment

with the fellowship of the dead.

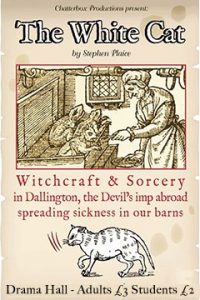

A 45 minute piece written especially for drama GCSE students at Peacehaven Community School.

The White Cat is a dramatized account of the witchcraft accusations made in Dallington, Sussex in the early seventeenth century. The play was directed by Jenny Alborough.

An opera in seven ‘fits’

On the site of the forgotten Mysteries of Lerna, the compulsive relationship between a man and a woman reawakens the buried gods. They have scented a sacrifice. Back in the city, the woman clings to her domestic routine, trying to come to terms with the terrible manifestation she experienced with the man in Greece …

Composer Sir Harrison Birtwistle

Libretto by Stephen Plaice

Directed by Stephen Langridge

Musical Director Alan Hacker

Designed by Alison Chitty

Lighting Design by Paul Pyant

Starring: Claire Booth, Amy Freston, Richard Morris, Joe Alessi, Teresa Banham, Sam McElroy

Quatuor Diotima

Première – Aldeburgh Festival: 11th June 2004

Press notices

‘Some of the most expressive music Birtwistle has written, and, as ever, there is the rich symbiosis between the gestures of the music and those depicted on stage. Vivid haunting and complex..the whole thing is a singular achievement.’

Andrew Clements The Guardian

‘Intellectually rivetting, musically groundbreaking, rich in mythological allusions that will send us scurrying back to our Ovids with renewed zeal’

Richard Morrison The Times

‘Weirdly compelling.. the sense of something dark being stirred into life, of violence tightly contained, was riveting. The beautifully-designed production seemed the perfect revelation of the work in all its vivid strangeness.’

The Independent

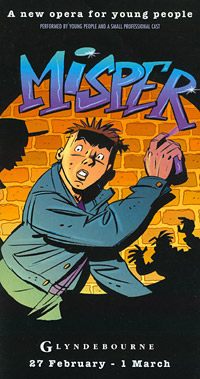

A children’s opera in six acts

When Chu Hsi (Misper), a 12th century Chinese philosopher, burns a hole in the manuscript of the history of the future he is writing, he unwittingly causes a train-wreck in present-day Crayford. He has to travel to the future to repair the damage. On Blackthorn Tip he befriends Frank Winter, the boy who has been falsely accused of causing the crash. He has run away from home and hidden at the tip.

Composer John Lunn

Book and lyrics Stephen Plaice

Directed by Stephen Langridge

Conducted by Andrea Quinn

Designed by Alison Chitty

Lighting Designer Keith Benson

Movement by Trevor Stuart

Starring: Omar Ebrahim, Josik Koc, Mary King, Tertia Sefton-Green, Melanie Pappenheim, Joss Turley, Gemma Ticehurst, Alice Purcell, Joseph Beamont, John Berry, Chris Hodges, Ben Davies

East Sussex Academy of Music Orchestra

Première – Glyndebourne: 27 February 1997

Revived at Glyndebourne: 25 February 1998

Press notices

‘Children’s opera has a chequered history. But Misper, commissioned by Glyndebourne and premiered by pupils from Sussex schools is a cracker. Stephen Plaice’s libretto brilliantly catches the way teenagers talk… this is one new opera that shouldn’t go missing.’

Richard Morrison The Times

‘Misper has more to offer than good looks; and whether or not it really counts as opera – ‘musical’ might be closer to the truth, it’s an impressive and affecting piece of work.

Michael White The Independent on Sunday

‘ At last, a teenage opera to sing about.’

Rupert Christiansen The Telegraph

‘Misper was a genuine show, staged with wit and gusto.’

The Independent

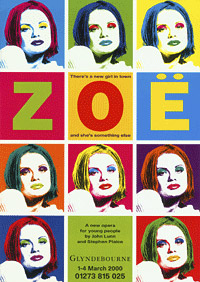

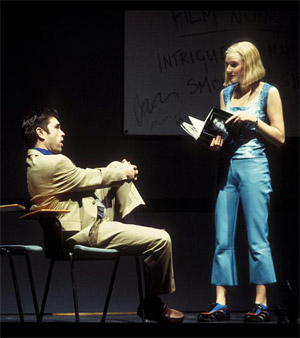

A teenage opera

Zoë, a young film student discovers that she has been cloned from a Hollywood film-star with whom her father, a genetic scientist, had been in love as a young man. She joins an eco-terrorist cell and vows revenge on her father and his company.

Composer John Lunn

Book and lyrics Stephen Plaice

Directed by Stephen Langridge

Conducted by James Morgan

Designed by Conor Murphy

Choreography by Vanessa Gray

Lighting Design by Keith Benson

Starring: Geoffrey Dolton, Fiona Campbell, Richard Coxon, Jonathan Viera, Daniel Gill, Emily Gilchrist, Gemma Ticehurst, Rebecca Bowden, Mark Enticknap

Brighton Youth Orchestra

Première: 1st March 2000

Press notices

‘Perfect Ten out of Teen. If I see another opera as enthralling as Zoe this year I shall count myself very lucky… Plaice, normally found supplying gritty slices of urban verismo for the Bill, has devised a story that moves swiftly and surely from tongue-in-cheek Raymond Chandler pastiche to a wild genetic nightmare, without ever straining credulity.’

Richard Morrison The Times

‘What a pleasure to experience something so enjoyable, so full of depth, angry energy, warmth and invention that the label ‘contemporary opera for teenagers’ seems inadequate. The exuberant, hard-hitting piece, more musical theatre than opera, held its audience gripped from start to finish. Standards were impressive, the energy infectious. The whoops and whistles were deserved’.

Fiona Maddocks The Observer

‘ The result, splendidly staged and perfromed by a mixture of energetic and accomplished professionals and young amateurs, is punchy and enjoyable.’

Rupert Christiansen The Telegraph

A hiphopera in two acts based on Cosí fan Tutte

This modern adaptation of the story transposes the action from Da Ponte’s original 18th century libretto to a 21st century inner city sink estate, where Liam and Freddie are invited by the manager of their crew, Big Donnie, to test the fidelity of their girlfriends Gigi and Bella. Mozart’s music rides the beats from the street. Da Ponte’s verse becomes authentic rap. But Despina is still Despina, and her philosophy remains: “by the time a girl is fifteen, she should know the ropes”.

The performance is aimed at young people of 14 years-old and above as it contains some strong language, deals with adult themes and has some sexual content.

Originally by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Lorenzo da Ponte

Idea and Concept : Markus Kosuch

Adaptation and Musical Arrangements : Jonathan Gill, Charlie Parker

Adaptation and Text : Stephen Plaice

Director : Claire Whistler

Designer and Lighting : Robin Carter

Conductor : Jonathan Gill

South Bank Sinfonia

Cast includes: Paradise (Donnie), Ville Salonen (Freddie), Jessica Walker (Gigi), Christine Gelder (Bella), Natasha Seale (Despina), Marvin Springer (Liam)

Première : Glyndebourne, 17 & 18 March 2006

Press notices

‘That this hip-hop reinvention of Mozart’s opera tapped into its tenderness, violence, passion and despair more powerfully than almost any Cosí I’ve seen was testimony to its success… this is one of the slickest and sassiest musicals around… The notion of morphing Mozart into the voice of an inner city prophet seemed risky in the extreme. But it has worked. And the sheer virtuosity of those metamorphoses in the musical arrangements of Charlie ‘the Baptist’ Parker and Jonathan Gill is striking, sometimes breathtaking… the updated story has spawned a text from Stephen Plaice that Mozart would have relished… This School for Lovers will be a hard act to follow.’

Hilary Finch The Times

‘The music promoter Donnie is played by the charismatic Paradise, who sets up exactly the right buzz of expectation, as does Stephen Plaice’s raunchy vernacular libretto… The overwhelmingly teenage audience was not disappointed. They loved the dance routines that periodically stopped the action, but they also liked those moments when Mozart came through with unadulterated clarity… This show will now go to Helsinki and Tallinn, but certainly deserves a further life in Britain. My teenage neighbour liked the Mozart bits, but she loved the club stuff best of all.’

Michael Church The Independent

‘What made it was the sharp contemporary wit of Stephen Plaice’s inner-city English text. I’ll never hear the duet for Dorabella and Guglielmo the same again now I know how well it fits the words.’

Richard Fairman The Financial Times

‘There are more good things to say about Glyndebourne’s hip-hop version of Mozart’s Cosí Fan Tutte than I have space available… I loved this West End-style production from the start. It was a hugely entertaining evening and I wish I could have bought a DVD recording of it as I left… Stephen Plaice’s witty and sexually explicit English libretto engaged the audience (a sea of young faces) throughout… the whole show was visually stunning and Glyndebourne must bring it back to Britain later in the year.’

Mike Howard Brighton Evening Argus

A children’s opera in two acts, comprising six tales

The analects of Confucius were blended with Chinese folk-tale to create a new children’s opera for Hackney Music Development Trust.

The Chinese Mother Goddess Nü Wa challenges Gong Gong the spirit of the water, and Jurong the spirit of fire to redress the balance of yin and yang in the human beings she creates out of the clay of the Yellow River.

They recount six tales to persuade her which of them she should favour in her recipe for the soul.

Cast: Nü Wa – Alison Buchanan, Jurong – Wu Yanmei (Mei Mei), Gong Gong – Damian Thantrey

Composer : Richard Taylor

Text : Stephen Plaice

Music Director : Jonathan Gill

Director : Clare Whistler

Designer : Neil Irish

Produced by Hackney Music Development Trust

Première: Hackney Empire July 3rd 2008

Winner of the Royal Philharmonic Society Award for Education 2008

A community opera in two acts

Lewes 2007, North Street Car Park, the former site of a naval prison. Early morning commuters converge under the ever-watchful eye of a town traffic warden. Lewes 1854, Lewes Naval Prison, the future site of the North Street car park. Three hundred prisoners of war from the Finnish Grenadier Rifle Battalion are in residence. In two years’ time, with the whole town of Lewes lining the streets to bid them farewell, they will return to Finland. The story of the kindnesses they received at the hands of the Lewes people will be immortalized in a Finnish national song.

Composer: Orlando Gough

Writer: Stephen Plaice

Directed by: Susannah Waters

Conductor: John Hancorn

Designer: Num Stibbe

Lighting: Clare O’Donoghue

Cast includes – Marcia Bellamy, Stephen Chaundy, Andrew Rupp, Joanna Songi and singers from the Finnish National Opera and Finnish Chamber Opera

Première: Phoenix Industrial Estate July 11th 2007

Press notices

Anyone hearing that Lewes had hosted a co-production with the Finnish National and Finnish Chamber Operas might reasonably assume we were talking about Glyndebourne. So it was quite a coup that the Paddock – a small local production company – to have secured such major international input into what is in essence a ‘community’ opera.

The actual link came when Plaice visited Helsinki himself and discovered the story of the Finnish Prisoners’ captivity in Lewes is remembered in one of Finland’s best-known folk-songs, the Oolannin Sota (Song of the Aland War), while his Finnish hosts were equally thrilled to hear that this episode in their history was being made into an opera in Sussex. Hence the co-production, the most audible result of which was the participation of eight Finnish singers as the POWs themselves.

In an opera whose plot is all about the power of love and lust to reach out across the gulfs of language, race, time and space, their very presence and hair-raisingly deep-toned rendition of the Oolannin Sota added an extra frisson of ethnic authenticity and vocal authority to the resonances already reverberating from the fact that the opera was being staged in a disused warehouse just yards from the site of the former prison (now a car park) where their 19th century compatriots were incarcerated, and just a few yards further from the surviving memorial to 28 of their number who died in captivity.

But if the Finns’ singing of the Oolanin Sota was an undoubted highpoint of the opera, it was only one among many.

Mark Pappenheim, Opera

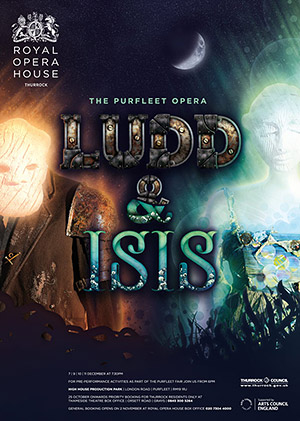

A community opera for the opening of the ROH Production Park at Thurrock

Composer: Richard Taylor

Librettist : Stephen Plaice

Director: Tom Guthrie

Designer: Rhys Jarman

Cast:

Ludd – James Oldfield

Isis – Tamsin Dalley

Stoker – Andrew Slater

Jo – Cheryl Enever

Edgar – Andrew Rees

Mrs Grantham – Sarah Pring

Upper River Nymph – Nicola Wydenbach

Lower River Nymph – Claire McCaldin

Digby/Kittywake – Robert Burt

Manyships/ Harry – Grant Doyle

Prow – Simon Lobelson

Dancers of the Royal Ballet:

Jo – Mara Galeazzi, Laura Morera

Edgar – Ryoichi Hirano, Bennet Gartside

Thurrock Community Chorus

Première: ROH Production Park Purfleet 6th November 2010

Review

‘Serendipity perhaps, but this year both of LondonÆs opera companies have taken over buildings far to the east of their normal homes for new operas. Where English National Opera in the summer teamed up with immersive proponents Punchdrunk in a deserted office block at Gallions Reach in Docklands for Thorsten RaschÆs “The Duchess of Malfi”, the Royal Opera House here celebrates its brand-new production workshop in Purfleet (replacing its previous premises in Stratford, subject to compulsory purchase and now re-fashioned as part of the Olympic Park), with a community opera “Ludd and Isis”, composed by Richard Taylor to a libretto bursting with local allusions and references by Stephen Plaice.

I can unequivocally state which was the more enjoyable. “Ludd and Isis” wins by at least the 11 miles between the two venues. Involving copious members of the Purfleet community, including children who have been practicing for eighteen months, and performed in the central section of the tripartite Bob and Tamar Manoukian Production Workshop on the hillside banks of the Thames just west of the rising span of the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge, it was a moving evening.’

classicalsource.com

A dramatised episode from Genesis

Cast: Jeffrey Lloyd Roberts – tenor – Jakob

William Towers – counter-tenor – The Angel

Music – Harrison Birtwistle

Libretto – Stephen Plaice

RIAS Kammerchor

Musikfabrik conducted by Stefan Asbury

Première: Skt Thomas Kirche Leipzig 13th June 2010

The image of Jacob wrestling with the Angel is one of the most resonant in world literature. Harrison Birtwistle saw it in his mind’s eye, asked Stephen Plaice to open it out into a libretto – and wrote his cantata Angel Fighter to a commission for the Leipzig Bachfest. Its British première at the Proms Saturday Matinée revelaed this ‘dramatic episode from Genesis’ to be a bold and startling recreation of the Biblical incident. Plaice’s pungent words include the novelty of Enochian language the pre-lapsarian angelical language recorded in the journals of Dr Dee. The Angel tells Jacob ‘If man does not fight his God, how will he ever know him?’ … David Atherton directed his forces with all the clarity and high drama of the work itself.

Hilary Finch, The Times

‘Angel Fighter reflektiert Jakobs Kampf mit dem Engel am Fluss Jabbok, eine ungeheuer kraftvolle Episode des Alten Testaments, deren musikalisches Potenzial gleichwohl bislang unentdeckt blieb. Birtwistle gieÊt den Text, den ihm Stephen Plaice in schlichte, prachtvoll plastische Sätze von Lutherscher Wucht gebracht hat, in eine siebenteilige Bogenform, eine dramatische Kantate, ein kompaktes Oratorium, das ganz auf die beiden Protagonisten zugeschnitten ist…

Was uneingeschränkt auch für die Musiker der musikFabrik gilt: Birtwistle hat dem Ensemble eine orchestral gedachte Partitur auf den Leib geschrieben, mehr auf Mischung setzt die Instrumentation denn auf Spaltklang. Eine Haltung, die die üppige Akustik in der Thomaskirche noch stützt.

Machtvoller, packender, sensibler, vielschichtiger als das, was Dirigent Stefan Asbury aus diesem Material macht, kann Neue Musik kaum klingen.’

Peter Korfmacher, Leipziger Volkszeitung

An opera in eight scenes

A Teatro Nacional de São Carlos co-production with Culturgest

Première: 17th December 2010

Música : Luís Tinoco

Libreto : Stephen Plaice

Direcção musical : Joana Carneiro

Encenação, cenografia, desenho de luz e conceito multimédia : Rui Horta

Figurinos : Ricardo Preto

Vídeo : Guilherme Martins

Electrónica e desenho de som : Carlos Caires

Intérpretes :

Tula : Raquel Camarinha

Ruth : Eduarda Melo

Stephanie : Patricia Quinta

Howard : Hugo Oliveira

Padre : Job Tomé

Lee : João Rodrigues

Orquestra Sinfónica Portuguesa :

I Violinos : Pavel Arefiev, Laurentino Ivan Coca

Violas : Ceciliu Isfan, Rogério Gomes

Violoncelos : Irene Lima, Luís Clode

Contrabaixo : Petio Kalomenski

Flauta : Katharine Rawdon

Oboé : Ricardo Lopes

Clarinetes : Francisco Ribeiro, Jorge Trindade

Fagotes : Carolino Carreira

Trompa : Paulo Guerreiro

Trompete : Jorge Almeida

Trombone : Jarrett Butler

Percussão : Elizabeth Davis, Lídio Correia

Harpa: Carmen Cardeal

Piano : Nicholas Mcnair

Músico em cena : Nicholas McNair

Maestro assistente : Kodo Yamagishi

Pianista correpetidor : Nicholas Mcnair

Assistente de encenação e produção executiva : Cláudia Gaiolas

Caracterização : Jorge Bragada e Raquel Pavão para Face Off

Cabelos : Helena Vaz Pereira para Griffe Hairstyle

Máscaras : João Prazeres

Tradução do libreto : Marta Lisboa

Operação da legendagem : Catarina Lourenço

Assistente musical : Carla Lourenço

Uma encomenda da Culturgest

Co-produção Teatro Nacional de São Carlos, Culturgest

A minha ideia para Paint Me (Pinta-me) era juntar seis personagens, todas com uma vida interior bastante criativa e fértil, e explorar o que é que elas pensariam umas das outras quando limitadas a um compartimento de comboio. O modelo formal do meu libreto é a obra The Canterbury Tales, escrita por Geoffrey Chaucer no século XIV.

Os viajantes de Paint Me também vão a caminho de Canterbury, mas a diferença é que estes são estranhos que foram agrupados em virtude da aleatoriedade da forma de viajar moderna, e os seus contos são narrados para si próprios, nas suas próprias fantasias.

Na idade moderna, quase todas as viagens realizadas por indivíduos são conduzidas em silêncio e anonimamente. Cada um de nós tem apenas acesso a uma impressão visual ou aos maneirismos das pessoas que se sentam à sua frente. Esta introspecção em público abre um espaço de fantasia privado, no qual os nossos companheiros de viagem se podem tornar personagens de breves dramatizações psicológicas.

Tentei, sim, dar o formato de uma narrativa completa às fantasias de cada uma das personagens. O resultado é uma espécie de antologia de short stories em forma de ópera, enquadrada no contexto de uma vulgar viagem.

Stephen Plaice

My idea in writing Paint Me was to bring together six characters, all of whom have a prolific imaginative interior life, and to explore what they would make of each other in the confines of a railway compartment.

The model for my libretto is Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. The travellers in Paint Me are also on their way to Canterbury, but they are strangers thrown together by the randomness of modern travel. Their tales are not told publicly, but in their own imaginations.

Most journeys in the modern age are anonymous and conducted in silence. We have only a visual or perhaps manneristic impression of the people sitting opposite us. This introspection in public opens up a private fantasy space, in which our fellow travellers can become the characters in instant psychological dramatisations.

I wanted to formalize each character’s fantasy into a full narrative. The result is a kind of anthology of operatic short stories, surrounded by the framework of an ordinary journey.

Stephen Plaice

An opera in four scenes

Four couples from different times share the same courting path with one another.

Première: Birley Centre Eastbourne October 14th 2012

Glyndebourne Jerwood Studio October 20th 2012

Composer: Luke Styles

Libretto: Stephen Plaice

Director: Tom Guthrie

Music Director: Lee Reynolds

Costume and Design: Kitty Callister

Lighting: Clare O’Donoghue

Pianist: Ashley Beauchamp

Cast:

Ellen Stanford – Millie Carden

Thomas Pulborough – Billy Charlesworth

Nial – James Brock

Prisha – Rebecca Leggett

Colin – James Eustace

Janet – Helen Lacey

Martin – Robert Haworth-Dunne

Zak – Lydia Hague

Carlotta – Lucy Burrows

An opera in six scenes

To pay for his newly renovated theatre, John Kemble attempts to stage an Italian Opera in the Theatre Royal Covent Garden, while the audience demands the restoration of the Old Prices and the old familiar shows.

Première: Royal Opera House main stage July 22nd 2012

Artistic Director: Gareth Malone

Composer: Julian Grant

Librettist: Stephen Plaice

Director: Tom Guthrie

Choreography: Sarah Dowling

Lighting: Lucy Carter

Design: Rhys Jarman *

Costume: Lesley Ford *

Vocal Director: Lea Cornthwaite

* with design students from Thurrock and South Essex

Cast:

Gweneth-Ann Jeffers – Catalani / La Zaffetta

Heather Shipp – Henry Clifford / Ernesto

Andrew Rees – Mr Kemble /Alfredo

Richard Burkhard – Ernesto

Gareth Malone – Chorus Master

With:

Royal Opera House Youth Opera Company and Guests Artist Dancers from the Royal Ballet

Students of National Dance Centres for Advanced Training,The Lowry, The Place and Dance East

The Hallé Youth Orchestra, with members of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

‘The great achievement of all this enthusiastic and country-wide cross-collaboration was that it somehow all came together into a coherent dramatic and musical whole, with highly professional and committed performances from everyone concerned. Not for one moment did it smack of tokenism.’

Henrietta Bredin Opera

An opera in two acts

Winner of the RPS Award for Learning and Participation 2013

Composer: Orlando Gough

Libretto: Stephen Plaice

Conductor: Nicholas Collon

Director: Susannah Waters

Designers: Es Devlin & Bronia Housman

Lighting Designer: Paul Pyant

Video Designer: Finn Ross

Movement Director: Christopher Tudor

Press notices

‘Community operas have to fulfil two criteria. They need to challenge and excite their performers — mostly, as on this occasion, non-professionals — and they have to work as viable stage works in their own right. That is not as easy as it might sound, and it is to the credit of librettist Stephen Plaice, composer Orlando Gough and director Susannah Waters that their new piece, Imago, achieves both these aims … the opera is a genuine success, and should be revived as soon as possible.’

George Hall The Guardian

Photo: Robert Workman

‘The one full chorus number that brought the house down was the hilarious ‘A Capella Wedding’, lovingly crafted by librettist Stephen Plaice to play to Gough’s strengths and love of unaccompanied choral singing. Preparing this showstopper — which deserves an independent life — must have been a joy! “Dinga donga dinga donga dinga donga ding, this is your a capella wedding,” sing the riotously dressed wedding guests. Plaice has excelled himself, condensing a complete online wedding and reception into some six fun-filled minutes.

But there are serious themes and dilemmas underlying Imago. How do we feel about vicarious love between a dying 80-year-old woman and a teenage lad? Should we, as a society, applaud or fear the impact our online lives are having on ‘real life’? What are the parameters that parents should use when determining how to handle their children’s involvement in the online world? How do we teach our children to avoid the perils that seemingly lurk around every mouse-click? Inappropriate relationships and predatorial grooming have become part of our online landscape and Plaice and Gough have not sought to avoid some of the questions that are inevitably raised.

The way Imago has been constructed for its large choruses of both young and old people will probably militate against its getting much exposure in the ‘real’ operatic world. But that would be a shame. It is too good a piece to be put to rest after a mere four performances at Glyndebourne this week.’

Antony Craig Gramophone

Photo: Robert Workman

‘Ambitious, imaginative and well executed, Imago is Glyndebourne’s latest community opera.

Languishing in a care home, Elizabeth is offered an Imago system, a computer-linked visor which allows her to create her virtual self (the 18-year-old Lisette) that inhabits a cyberworld. After losing her way in a bout of gambling, and after shaking off a cyber-stalker, Lisette falls in love with Gulliver (whose real-world ‘host’ is the elder son of Elizabeth’s therapist). Gradually, Elizabeth becomes addicted to her younger avatar and, on her death, becomes one with her.

Gough’s score is often minimalist in style, with edgy wind and brass colouring repeated riffs, but there are plenty of intimate, lyrical moments too, and the music takes centre stage in the set-piece of Lisette and Gulliver’s doo-wop style a cappella wedding, complete with a hip pastor (radiantly sung by George Ikediashi). Finn Ross’s video animations, often running the full width and height of the three-tier set are brilliantly conceived and deftly integrated into the whole.

Jean Rigby sings warmly as the initially crabby Elizabeth, and sounds completely at ease in this (for her) relatively unfamiliar idiom — though she is not always audible. Joanna Songi is the bright-eyed Lisette with a voice to match. With a fruity baritone and solid stage presence, Adam Gilbert impresses as Gulliver. Nicholas Collon conducts a 19-piece Aurora Orchestra, swelled to more than double that number by young student musicians.

There may be some small storytelling details that need sharpening in this intergenerational undertaking, but it’s a very smart, collaboratively conceived production that has hit the ground running.’

Edward Bhesania, The Stage

A fifteen minute ’Snappy Opera’

A short children’s opera which forms part of Snappy Operas, a project created by for primary school children by Mahogany Opera in 2017.

Stephen wrote the opera in collaboration with the composer Jamie Man. A dormitory of children are counting sheep trying to get off to sleep. But unfortunately a group of ramblers leave the gate open. The sheep start to roam the universe and decide to play moonball.

The project has gone on to tour schools up and down the country.

A sample poem from the collection

Rumours of Cousins

At thirty we long to begin again,

to bring order to our bookshelves

and tinker with our dormant convictions,

but instead the children come crying

into the silence where we once read,

demanding where we ourselves demanded,

and our lives spread out like magazines

with regular features but no great themes.

Eventually living follows thought no longer,

but thought living, and stronger links

chain our thoughts to the everyday.

We find ourselves absorbed in manuals,

descriptions of the hardy annuals,

or the many reasons recipes fail.

We make our daily diet substantial,

take pleasure in the meals and bedtimes,

in waking with the same arms round us,

for we may now afford ourselves some comfort

and approve at last our own familiar reality

condensing around the kitchen table.

To be the author of all this flesh

has brought a certain happiness,

but sometimes weeding in a border,

or sorting in a confused cupboard,

sometimes at dusk drawing the curtains,

there come rumours of cousins,

possible existences long since terminated,

versed in spectacular philosophies,

polyglottal from continuous travel,

wearing the smile of another knowledge,

mysteries we may not now unravel.

Another moment and we would welcome them,

like a constellation on a clear night,

but the crying comes, the louder mortal crying,

and we begin again to fuss and mother,

pretending this is our one firm life,

denying rumours of the unlived others.

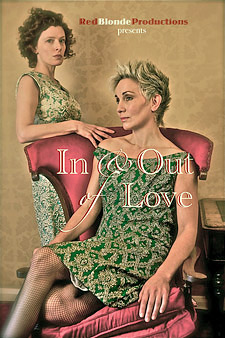

RedBlonde Productions

Written and directed by Stephen Plaice

Cast: Lila Palmer, Red Gray, John Grave, Marcia Bellamy

Musicians: Julian Broughton (piano), Ellie Blackshaw (violin)

Costume: Berthe Fortin

Lighting: Charlie Housego

Brighton Fringe Festival 2016, Church of the Annunciation

Don’t let the informality fool you, Stephen Plaice’s brilliant tale of the louche world of the Théâtre des Bouffe in 2nd Empire Paris enjoys the highest standards of performance and musicality. Top quality singers Lila Palmer (soprano), Jon Grave (tenor), Red Gray (soprano) and Marcia Bellamy (mezzo) relate the jolly yet poignant tale of a first-class courtesan, Hortense Schneider.

Their delightful selection of songs by Offenbach, Donizetti and Martini are supported in grand style by Julian Broughton (piano) and Ellie Blackshaw (violin) who also provide expert cabaret beforehand. Sophisticated, charming and fun, a Parisian confection that’s not to be missed!

Rating: ★★★★★

Andrew Connal

The Latest, June 3, 2016

Première: Brighton Fringe Festival 2015, Church of the Annunciation

Low Down

What does Brighton Fringe make you think of?

Art and culture, certainly — but not stuffy and self-satisfied like the main Festival (Sorry!). No, Fringe is smaller scale, hugely enthusiastic, more experimental, edgier — and usually a lot more fun! In fact, the best word to describe it would be … Bouffe!

Review

Bouffe is a form of operetta developed by Jacques Offenbach in Paris in the 1850s. Small scale, with only three or four singers, and much shorter works than the full-scale operas being produced at the time. Offenbach found a little theatre on the Champs-Élysées and started producing light, comic pieces, usually of just one act, with plots about love affairs or seductions.

‘La Belle Hélène’, ‘La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein’ and ‘La Périchole’ followed each other in quick succession over a few years, pulling in the Parisian punters off the boulevards and making Offenbach a great deal of money. They came to listen to the singing, true, but they certainly also came to gaze at the singers, and often to do more than just gaze …

So ‘Bouffe!’ is a show with all the Ps — Performance, Paris … and Prostitution. Actresses and singers of that era were generally regarded as being sexually available, and many made fortunes as courtesans, offering their favours to wealthy or aristocratic patrons. One of the greatest — both as a soprano and as a courtesan — was Hortense Schneider. Reputedly a mistress of The Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII, she had so many aristocratic admirers that she became known as ‘La Passage de Princes’ — ‘The Arcade of Princes’ —– a pun on a high-class arcade in Paris.

So this is the show that RedBlonde Productions are putting on. A show featuring Hortense Schneider. And they’re doing it in a church? Blimey!

But why not? If a consecrated space is good enough for Mary Magdalene …

Actually, The Church of the Annunciation is a wonderful choice of venue, with its high wooden hammerbeam roof and its spacious interior. When the house lights went down we had warm sunlight illuminating the beautiful stained glass windows, gradually fading as the evening turned to night.

RedBlonde have done ‘Bouffe!’ as a sort of promenade performance. They’d set up a Parisian café at one side of the nave, with blue gingham tablecloths on the tables as we sat with our drinks — there was a bar, too. A waitress moved around the tables, a piano and a violin were providing background music, and then the ‘Patron’ emerged, in black tie and tails, and explained — in song — about the phenomenon of Bouffe.

Marcia Bellamy is a striking woman at any distance, close up she’s unforgettable. A great shock of blonde hair, set high above her head, her hands very mobile and expressive as she sang – she’s a great actress as well. Then the waitress took up the words, too, at the other end of the café, and we had a mezzo-soprano (Bellamy) and a soprano (Red Gray) giving us the full stereo rendition of songs like ‘Mon Dieu! Que les hommes sont bêtes’ (‘God!, men are beasts’).

And they are. We left the Café and took our seats on the pews in the nave of the church. ‘Bouffe!’ opens with an audition — the hopeful Cécile (Gray) is singing, and the theatre’s owner isn’t impressed. “We’ll let you know”. Bellamy was in grey trousers and shirtsleeves for this bit, with a cigar chomped between her teeth. She had an amazing number of costume changes in this production — she’ll need to add ‘quick-change artist’ to her portfolio.

Cécile is dismissed, and Hortense comes on next. We’d seen Lila Palmer in the café, sitting quietly at a table with her book, but we hadn’t taken much notice. Now she sang some Donizetti for her audition piece, and the theatre owner was much more interested. Not just in her singing, either. Cécile has been watching, and gives Hortense some advice — she’s still wearing her outdoor coat — “They don’t just come to hear your singing. Show more … wear less.”

So the situation is set. Hortense has just arrived in Paris, so she moves in with Cécile to share her apartment. In an unforgettable scene, they celebrate their new friendship by getting very drunk. Two women, one dark haired (Palmer), one redhead (Gray). Two soprano voices, powerful but perfectly controlled, pouring absinthe into themselves and pouring the great music of Donizetti down into the nave of the church, washing over us.

It can’t last, of course. Not in opera. Cécile has a lover, Jean-François, and as soon as he arrives at the apartment he’s smitten by Hortense. Jon Grave’s expressive tenor voice can do passion but it can also do innuendo, and the three launch into a song ostensibly about flying a kite — though it’s full of double entendres. This piece was written by Offenbach himself, but one of the many joys of this production is that the director, Stephen Plaice, is also a very accomplished librettist and translator, and he’s given us the words in English, which made the story much easier to follow.

Plaice has done this with a number of the songs, generally at a point where some kind of exposition is required, so we had the double benefit of beautiful singing in the original French or Italian, then reverting to English for storyline — without the usual operatic need for surtitles or scrabbling to look at our programmes. The acted, spoken bits were of course all done in English. The company made imaginative use of the space within the Church, too, with a main acting area in front of the altar, but making exits and entrances through the chapels on either side, and moving down into the nave along the aisle and even commandeering several of the pew seats.

Hortense gets taken up by Offenbach in his Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, becoming renowned as a singer, but also as an alluring beauty. Jean-François is drawn to her ‘like a bee to a jampot’, and poor Cécile has to put on a brave face. Eventually, of course, Hortense is taken up by the elegant, rich Duc de Gramont Caderousse. Bellamy played this in a shimmering grey morning suit and top hat, stick always in hand. Her every expression and gesture effortlessly aristocratic. I was reminded of Proust’s great creation, Monsieur Swann – he was besotted by an actress, too – and he was a friend of the Prince of Wales …

You don’t really need the rest of the plot — suffice to say that Hortense got pregnant, and later very rich, and there were betrayals and reconciliations, all the stuff of authentic operetta. Real Opéra Bouffe, in fact. What you do need to know is that the musical accompaniment was provided by Ellie Blackshaw on violin and Julian Broughton on piano. They’d provided background in the Café at the start, and later their music filled the nave of the Church, making a perfect frame for the picture being painted by the two sopranos, the mezzo soprano and the tenor. Great performances of Donizetti, Martini, and of course mostly of the great Jacques Offenbach himself.

If you missed this, you should be kicking yourself. Hopefully ‘Bouffe!’ will be given another set of performances. Please!

Stephen has participated in many education projects for Glyndebourne, including the production of the musical Race the Devil for the Arundel Festival in 1995, which was a collaboration between probationers and drama students, with the composer Adrian Johnstone. It told the legendary Sussex story of Micky Miles who raced the Devil across Leonardslee Forest in order to save his soul.

Between 1995 and 2005, Stephen wrote the following episodes of ITV’s The Bill :

Half-hour episodes

Four Walls 1995

Lockdown 1995

Follow the Van 1996

Toe the Line 1996

Parklife 1997

Last Respects 1997

Stolen Thunder 1997

One of the Gang 1998

Under the Grill 1998

Hour-long episodes

The Wrong Horse 1999

Tinderbox 1999

Borderline 1999

Sun Hill Boulevard 1999

Search Me 2000

Trust (3 Parter) 2000

The Leopard (2 parter) 2001

Return of the Hunter 2001

Angel Rooms 2001

On a Clear day (2 of 3 parter) 2001

Lifelines 2001

Episode 293 2005

A three-hander that dramatises the extraordinary marriage between John Galsworthy and his wife Ada. At the same time Galsworthy was involving himself in the social reform of solitary confinement, he had become a prisoner of his own marriage.

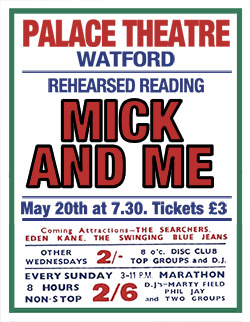

Set during the Stones tour of 1964, a Watford schoolboy strikes up an unlikely friendship with one of the band.

Mick is as trapped by his celebrity status as his new friend is by his existentialist isolation in his home town. They realize they both want a piece of each other’s life.

A rehearsed reading of Stephen Plaice’s new play was held at Watford Palace Theatre on May 20th 2009

In recent years, since the filming of Joseph Conrad’s Amy Foster, under the title of Swept From The Sea in 1998, the true location for his rather neglected novella has been obscured behind the Hollywood version starring Rachel Weisz. The film was shot in Romantic Cornwall, and Amy herself is given a mysterious Celtic personality quite unlike the woman Conrad sets at the heart of his story. Presumably, the producers considered the Kent coast too tame and prosaic a backdrop for their film. As part of my research for Amy, a new opera for the Royal Swedish Opera for which I am supplying the libretto, I decided I would try to pinpoint where Conrad had actually set the original story. This research led me to the Kent coast, not far from Pent Farm, where Conrad was living in 1901, the year he wrote Amy Foster.

Conrad had been inspired to write the story after reading an anecdote in Ford Madox Ford’s book The Cinque Ports, a historical and descriptive account of the favoured trading ports on the Kent and Sussex Coasts. Ford mentions a shipwrecked sailor from a German merchant ship who spoke no English being driven out by the local population and finding refuge in a pigsty. This unfortunate sailor was the model for Yanko Gooral, the émigré husband of Amy Foster. If Conrad was using a real event as the basis of his story, I reasoned, wouldn’t he use real locations too? There was of course the possibility that Conrad had used generic details from that costal region to create fictional locations – the Martello Towers, the coastguard cottages, for example. But might he not also have used the real models of places that he had visited and knew well from his wanderings around Pent?

In the novella, Conrad describes two coastal villages, one called Colebrook and one called Brenzett, visible to each other across the large bay in the Channel which Conrad calls Eastbay in the story. There is a real Brenzett, a hamlet some miles from the Kent Coast, with none of the topography from the story. Conrad, who claimed he never kept a notebook, but wrote from memory, has clearly borrowed the name and applied it to the rougher coastal village where Amy lives. Doctor Kennedy, one of the liberal influences in the story, lives in the more affluent Colebrook, just across the bay. The question I wanted to answer was: did Colebrook and Brenzett disguise two real places on the Kent Coast? So I set off to examine the coastal towns closest to the farmhouse.

Colebrook

There are two descriptive passages in the story about Colebrook:

1) The high ground rising abruptly behind the red roofs of the little town crowds the quaint High Street against the wall which defends it from the sea. Beyond the sea-wall there curves for miles in a vast and regular sweep the barren beach of shingle, with the village of Brenzett standing out darkly across the water, a spire in a clump of trees; and still further out the perpendicular column of a lighthouse, looking in the distance no bigger than a lead pencil, marks the vanishing-point of the land.

2) The brow of the upland overtops the square tower of the Colebrook Church. The slope is green and looped by a white road. Ascending along this road, you open a valley broad and shallow, a wide green trough of pastures and hedges merging inland into a vista of purple tints and flowing lines closing the view.

These are exact descriptions of the red-roofed coastal town of Hythe, the nearest conurbation to The Pent, the farmhouse where Conrad lived with his family between 1898-1908, and where he wrote many of his major books. Hythe was only three miles away. It has a sea wall, from where looking south east, along ‘a vast and regular sweep’ of shoreline, you can just pick out the new lighthouse at Dungeness, ‘the vanishing-point of the land’. This is not the structure that Conrad would have seen, of course, which he describes as ‘no bigger than a lead pencil’; he would have seen an earlier structure built in the eighteenth century, a mere 116ft tall. A new lighthouse, the precursor to the modern one, had been commissioned at Dungeness the year that Conrad published Amy Foster but would not yet have been visible.

Geographically, Hythe is situated below the final escarpment of the Kent Downs before they reach the sea. The old London Road from Hythe runs inland, ascending into the Kent Downs, just as Conrad describes in the story. Standing high above the still quaint High Street, the church of St Leonard dominates the town, but it is itself underneath the brow of the hill. Conrad had frequent business in the town. His son Borys was christened at Hythe Catholic Church. He frequently owed money to tradesmen in the town. It was a place he got to know well.

Having identified Hythe as Colebrook, I began to realize that Conrad had set Amy Foster very much in his own backyard. I then turned my attention to Brenzett.

Brenzett

In the curve of the coast between Hythe and Dungeness, the village of Dymchurch is visible, ‘standing out darkly across the water’. Here is Conrad’s description of the village onto which he transposed the name of Brenzett.

The country at the back of Brenzett is low and flat, but the bay is fairly well sheltered from the seas, and occasionally a big ship, windbound or through stress of weather, makes use of the anchoring ground a mile and a half due north from you as you stand at the back door of the “Ship Inn” in Brenzett. A dilapidated windmill near by lifting its shattered arms from a mound no loftier than a rubbish heap, and a Martello tower squatting at the water’s edge half a mile to the south of the Coastguard cottages, are familiar to the skippers of small craft. These are the official seamarks for the patch of trustworthy bottom represented on the Admiralty charts by an irregular oval of dots enclosing several figures six, with a tiny anchor engraved among them, and the legend “mud and shells” over all.

I drove from Hythe along the coast road to Dymchurch. To my astonishment, just before arriving in the modern centre of the village, I came across The Ship Inn, still standing directly opposite the Norman church of St Peter and St Paul, located in what must have once been the heart of the village. Dymchurch rapidly expanded south as a day-tripper’s resort in the 1930s, after the building of the Romney Hythe and Dymchurch railway. But the village Conrad would have seen was a thin straggle of houses along the road on either side of the church. It is now known as Church End. In 1908, less than a decade after Conrad must have visited from Pent, Walter Jerrold described the village as ‘a quiet scattered village and a delightful place far from the madding crowd’. It had a bohemian reputation in the early years of the century, attracting writers and actors and artists including Paul Nash.

Although it is now buffered by a new housing estate, Ship Close, the beach, still with its sea-wall, is only a stone’s throw away from the back entrance of The Ship Inn itself. In Conrad’s day, there would have been a clear view of the sea, all the way to Hythe, to the north, and to Dungeness in the south. But the clinching piece of evidence is that Conrad retained the inn’s real name which it still keeps today, advertising itself as a ‘five hundred-year-old inn.’

The Church of St Peter and Paul, almost directly opposite the Inn stands amongst mature trees. It has a dumpy spire. It matches the description ‘a spire in a clump of trees’. This part of the old village is a clear fit for Conrad’s Brenzett.

But there are some details that can no longer be verified, or perhaps they are additions by Conrad transposed from elsewhere in the vicinity. There is no longer any evidence of a windmill in Dymchurch, though neighbouring New Romney once boasted seven, and it seems reasonable to assume that Dymchurch had windmills too, transitory structures at the best of times. I am also unable to pinpoint exactly which tower is referred to in the clause ‘a Martello tower squatting at the water’s edge half a mile to the south of the coastguard cottages’. But both Martello towers and the coastguard cottages are prevalent features of the locality.

Martello Tower 24 – The Old Coastguard Station

Martello Towers were built as coastal defences during the Napoleonic Wars. In the early nineteenth century, the coastline at Dymchurch had no fewer than eight of them, of which only three remain today, numbers 23,24,25. Already by the time of Conrad’s visit some of Dymchurch’s towers had fallen into disrepair, had been demolished or had been lost to the sea. Martello Tower 24 was used as the Old Coastguard Station during Conrad’s day. Although there appear to be no longer any coastguard cottages standing in Dymchurch itself, they are very much a feature of the locality. The nearest coastguard cottages I could find still extant are at Littlestone, a little further south from Dymchurch.

Martello Tower 25 Dymchurch

Of course there is no reason that every detail of the description given in Amy Foster should map perfectly onto the real landscape, but it is remarkable how much of the real topographical detail Conrad has retained, leaving no doubt in my mind, having visited the real locations, with their Martello Towers, Coastguard Cottages, churches and lighthouse, that Conrad has set his story firmly in the Romney Marshes.

Perceptively, Bertrand Russell described the story of Amy Foster as the key to Conrad’s own psychology. The author appears to have enjoyed the house at Pent, and the beauty of the surrounding landscape, but did he, as an émigré, experience hostility from the local inhabitants? Conrad never lost his accent or his ‘foreignness’, and even though he wrote superlative English prose, he never felt accepted by the English themselves. During his nine years in coastal Kent, did he suffer the same prejudice at the hands of the locals as his unfortunate protagonist Yanko? What we can now say is that Conrad’s choice of the moody marshes, and their darkly begrudging inhabitants, was closely based on real geography.

John Galsworthy at Lewes Prison

The concept of Writers in Prisons has flourished in Britain in the last decade. But, like so many other initiatives on the treadmill of penal history, permission for writers to enter prisons is by no means a recent innovation. There are those who had the primary experience, of course, Bunyan, Defoe, Wilde, Behan, Orton, who made use of it for literature. But there are also those, following in Dickens’ footsteps, who visited and, as a result of their experience, earnestly engaged with the idea of prison reform.